The Researcher Passport: A Digital Credential to Improve Restricted Data Access

Margaret C. Levenstein

Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research

Allison R. B. Tyler

Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research

Johanna Davidson Bleckman

Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research

2019

Problem Statement

In the last two decades, research data repositories joined libraries and archives in promoting access to and use of data by making it available directly on the internet. While this led to a radical expansion in the availability of data resources, providing such access is increasingly limited by the need to protect privacy, security, or property rights. These challenges are particularly acute for researchers using social media data, for which there are often issues of both privacy and property rights. More generally, these issues arise when researchers use non-designed, organic data that are the digital traces of daily life. The existence of such data makes possible research that may provide important new insights into human behavior. But doing so ethically and responsibly requires that we adopt consistent practices for researchers to manage such data and consistent terms under which repositories provide researchers with access to them.

The access challenge is magnified when researchers require data sets from multiple data repositories, each of which has its own access requirements. There is often inconsistency between data custodians in the information they require from users, whether the required information is validated, how restrictions are characterized, and how data are accessed. These inconsistencies make it difficult and time-consuming for researchers and repository staff, because they require duplicate effort by both parties to request and grant access to similar data with different requirements.

To better understand this challenge, the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) conducted a year-long study of 23 restricted data repositories around the world. The environmental scan and interviews encompassed government and academic data repositories that hold bio-medical, administrative, labor and unemployment, drug use, and census data from five countries which currently provide digital access to restricted data. Several repositories were investigating solutions to the data access challenge at the time of the study, and we were interested to learn more about how they were approaching the challenge of accessing and using multiple restricted data sets while maintaining security and privacy. Through a thorough analysis of repository policies and procedures and a series of in-depth interviews with repository staff, we identified three specific areas in the data access process that hinder efficient data access across multiple institutions:

- User verification

- Training requirements

- Terminology

For each of these areas, no two repositories used the same processes or interpretations of legal and regulatory requirements. Data users who need data from multiple sources must negotiate the data access processes, each with their own requirements and expectations, multiple times, duplicating their efforts and delaying their research projects as they wait for the repositories to complete their own processes.

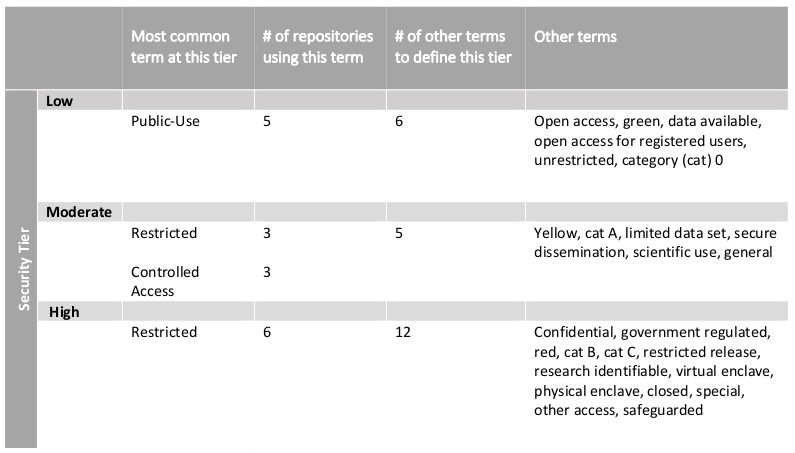

Repositories require verification of different information about users as they review data access requests. Some repositories require in-depth background checks, while others simply validate the application information with the user’s institutional web sites. There are also different expectations for users’ levels of experience in working with restricted data: of the 23 repositories, only 6 required reporting any type of data management training, though all interviewees agreed that a minimal level of experience was highly recommended (Levenstein, Tyler, and Davidson Bleckman 2018). Finally, restricted data repositories do not use the same terminology to classify their data along a low-to-high data security spectrum (see Table 1). “Restricted,” for example, meant moderate security at three repositories, and much higher security at six. With no consistently applied standard for repositories, there is little rationale for individual repositories to accept an approved data user from another repository as a means of improving efficiency for data users and for the repository.

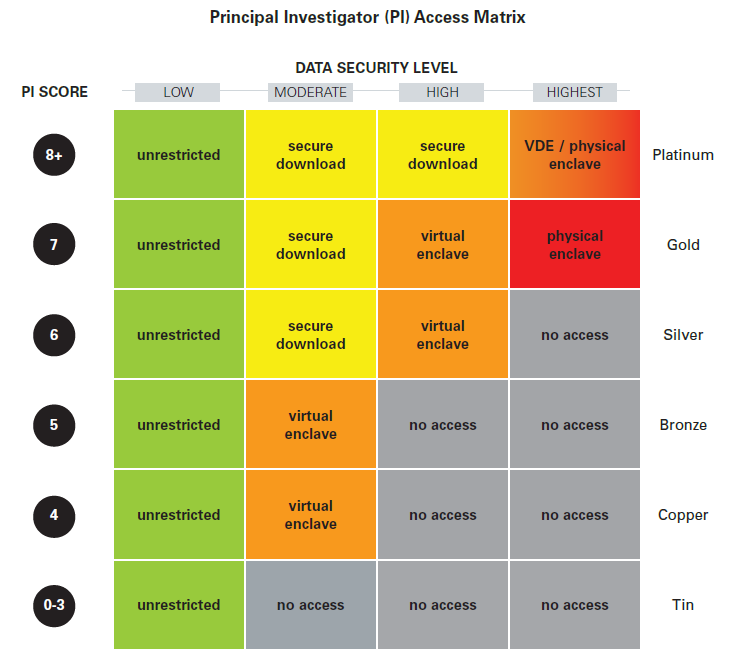

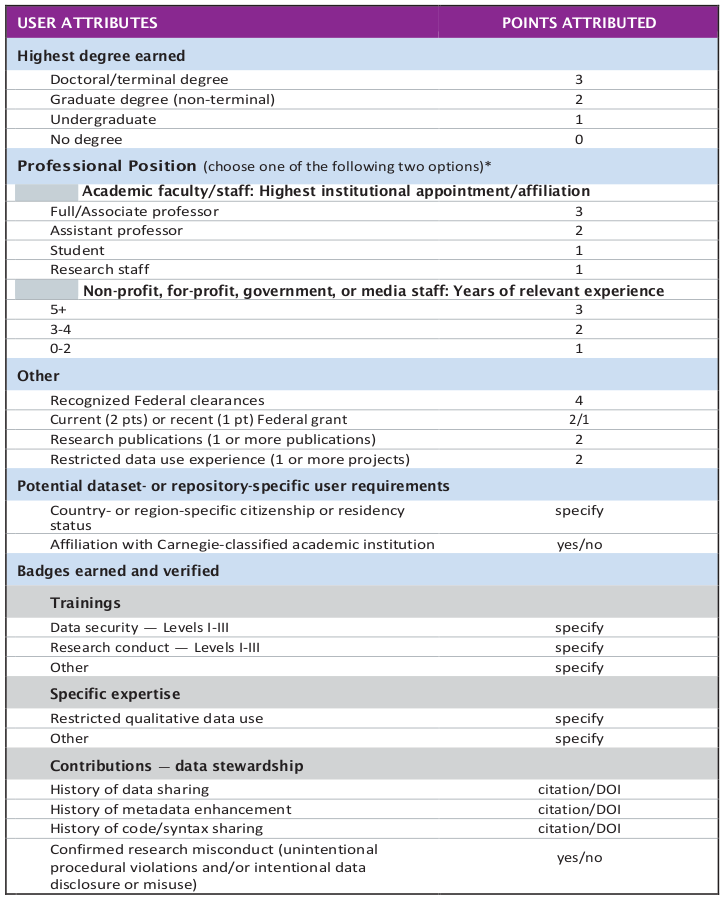

To solve these challenges and promote a research community with a shared understanding of the needs of researchers and repositories, ICPSR is developing the Researcher Passport. This digital identifier captures verified information about the user, which, when shared within and across the community of restricted data repositories, can minimize the time-consuming and redundant identity verification step of the data access request process. Information about the user will be embedded within the Researcher Passport through a system of open badges which indicate verified and unverified identity information, completed training, and prior experience with restricted data. Based on a matrix of user criteria, users will be granted a Researcher Passport of a certain level (e.g., tin, bronze, silver, gold, or platinum) that serves as a measure of trust, commensurate with the passport holder’s credentials. This passport level is then used by the data repository in evaluating the data access request. If the passport level and the project meet the repository requirements, the repository issues a Visa that authorizes the Passport holder to access the desired data in a particular computing environment for a specified period of time.

Researcher passport

The foundation of the Researcher Passport is the level of trust that data repositories place on their users: the more the repository trusts the user to use data in accordance with the data use agreements, based on data use experience and professional and academic qualifications, the more willing the repository is to grant the user access to the requested data. The Researcher Passport will be the trusted digital identity that tells repositories that the user’s identity (including name, institutional affiliation, academic and professional qualifications, research experience, and data security and data management training) has been verified. The passport level, described below, serves as an indicator of the recommended level of trust that the repository can place on an authenticated user, and unlike the current process where each repository determines that trust individually with each separate access request, the trusted, authenticated user identity can be shared between institutions participating in the Researcher Passport.

The first time that a user requires restricted data from a participating institution, the user submits an application to ICPSR for a Researcher Passport. ICPSR conducts the in-depth identity verification process and issues a Passport at the applicable passport level (see Appendix A). Specific, verified components will be identified within the Passport, and users will consent to this information being shared between institutions as they make their decisions about access to specific data sets. Once the Passport is issued, the Passport level represents the standardized data security classifications and associated recommended access methods for the designated Passport level. Throughout a Passport holder’s data use career, elements of their passport—institutional affiliation, years of professional experience, academic qualifications, history of data use and data stewardship—are updated and re-evaluated, and the Passport level adjusted accordingly.

This Passport does not replace the authority of repositories to implement their own additional requirements for information about users or the project proposal, nor does it mandate that any user who is issued a Passport be granted access to any and all data for which they might be eligible. As part of the Researcher Passport, ICPSR recommends standardizing the metrics for determining the data security level for data sets, discussed further below. By standardizing how repositories understand and interpret low, medium, and high security levels, the record of a user’s access to a “high” security data set, for example, can be understood by other repositories when evaluating the Passport information. These levels are flexible to the specific needs of the repositories, to that repositories can review the project descriptions and the need for the data, and measure the Passport recommendation against their requirements for the data before they issue a Visa. If a user’s Passport does not include a badge for a repository-specific access requirement, e.g., a specific type of training certificate or an additional piece of identity information, even if they meet all other requirements, the repository simply does not issue the Visa. The user must submit the missing information in addition to their Passport and request that the repository re-evaluate.

Within the Researcher Passport system, the Visa is what authorizes access to the data in the repository. Over time, as users access data, the Passport’s visas also serve as the record of prior data use that some repositories already require as part of the data access request process.

ICPSR is developing this system within the ICPSR infrastructure. In November 2018 ICPSR will launch phase 1 of the Researcher Passport as part of its ICPSR MyData user accounts.The existing user base of 60,000 active MyData account holders will facilitate dissemination and adoption of the Researcher Passport necessary to establish the passport as a shared norm for defining trusted researchers.

The system will be piloted at three restricted data repositories: ICPSR and the Institute for Research on Innovation & Science (IRIS), both based at the University of Michigan, and the Qualitative Data Repository, at Syracuse University. Adjustments to the verification and credentialing processes will be made based on evaluation of these pilots. The repository community will then be expanded to include other institutions.

Open Badges

An innovative component of ICPSR’s Researcher Passport is the use of Open Badgeshttps://openbadges.org/

as the mechanism for embedding user characteristics—identity information, academic qualifications, professional experience, training completion—within the Passport. The Passport is the digital container for these badges. As part of the initial Passport issuing process, select badges will be identified as “verified.” Verified badges will include the components of data access requests that were identified as most important for developing trust in potential users (Levenstein, Tyler, and Davidson Bleckman 2018). Badges can be used by repositories in defining their access requirements. If an applicant does not meet the badge requirements for specific data sets or access methods, then further review is required to determine which access method would be appropriate, or if access should be granted at all. Beginning in 2019, ICPSR and the University of Michigan School of Information will build and integrate ICPSR badges into the Passport.

Community Norms

In addition to the benefits to repositories and data users in terms of more efficient data access request evaluation and user authorization, the Researcher Passport project seeks to establish shared norms and expectations around the access and use of restricted data. The Researcher Passport is most useful if it is widely accepted by the repository community; the more it is accepted and implemented, the more standardized the expectations will be. Our analysis of existing repository practices identified three specific areas where this standardization is needed and for which the Researcher Passport provides that standardization:

- User evaluation criteria

- Data evaluation criteria

- Data management training

User evaluation criteria

First, we propose a point-based user evaluation process to determine the Passport level eligibility. Passport applications are reviewed and points assigned based on the highest academic degree earned, the professional position (with separate attributes for non-academic researchers, e.g., media, non-profit, for-profit, and government employees), possession of a government-issued clearance, history of federal grants, publication history, and restricted data use experience (Appendix B). Badges will be indicate these attributes, as well as additional attributes relevant for access to specific data sets but not necessary for the Passport level determination (e.g., nationality).

Data evaluation criteria

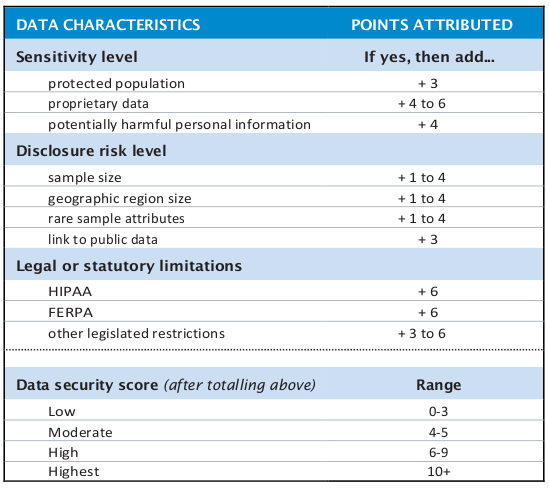

Similarly, we propose standardizing the data security level assignment process. Currently, as discussed above and in Table 1, there are a wide variety of terms and interpretations of data security levels, based on repository naming conventions and the specific needs of the data set in question. We recommend a spectrum of Low, Moderate, High, and Highest, each of which has a point evaluation range comparable to the user evaluation criteria. Data sets will be reviewed for different characteristics including sensitivity, disclosure risk, and legal or statutory limitations; total points map to a data security level. An example of this metric can be viewed in Appendix C. This metric provides flexibility for repositories to add additional evaluation criteria (e.g., detailed geography, additional legal requirements); the data security score range is adjusted accordingly. This will build a common understanding of the meaning of data security levels, even as repositories maintain use of additional requirements for access to particular datasets.

Training

ICPSR evaluated the training requirements for access to restricted data at the 23 repositories in our study. Most repository training requirements refer to Human Subjects Research and Responsible Conduct of Research, in accordance with IRB requirements. We also evaluated the content of trainings required by repositories; we found only two that included content specifically focused on restricted data. In both cases, the training modules on restricted data were developed for use only at their specific institutions. Even in these training modules, data protection and data handling topics are discussed only briefly. No training program exists that covers all topics to which repositories said they wanted their restricted data users exposed. As part of the development of the Researcher Passport, ICPSR will develop training modules to meet the requirements and expectations of repositories. We will also continue to try to identify other training programs that meet these requirements. Completion of training will be identified through appropriate Badges on the Passport.

Conclusion

We live in a data-intensive world. We create data as we sleep and walk and eat, with every purchase we make, every email we send, every camera we stroll by. These data are valuable for research and evidence-building. Analyses of such data are used to inform more science and more policy making than ever. But it is also easier than ever to identify individuals, or use data inappropriately or inconsistently with the expectations of those being measured.

Given the unprecedented availability of digital data and the continuing need to interrogate “old” data, secure and efficient mediation of data access is a priority for the research community. ICPSR’s development of the Researcher Passport, a digital researcher credential based on shared norms about users and about data, represents our contribution to the challenge of balancing access and privacy. The process begins with developing a shared understanding of how data are classified and how users are evaluated and authorized to access that data, and then turns to the design and implementation of a system that operationalizes the trust imbued in those users in a digital identifier.

For further details about the researcher credentialing research project, please consult our May 2018 report to the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, available at https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/143808.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

Levenstein, Margaret, Allison R. B. Tyler, and Johanna Davidson Bleckman. 2018. “The Researcher Passport: Improving Data Access and Confidentiality Protection.” ICPSR White Paper Series No. 1. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/143808.